Origins of the True Value adjudication

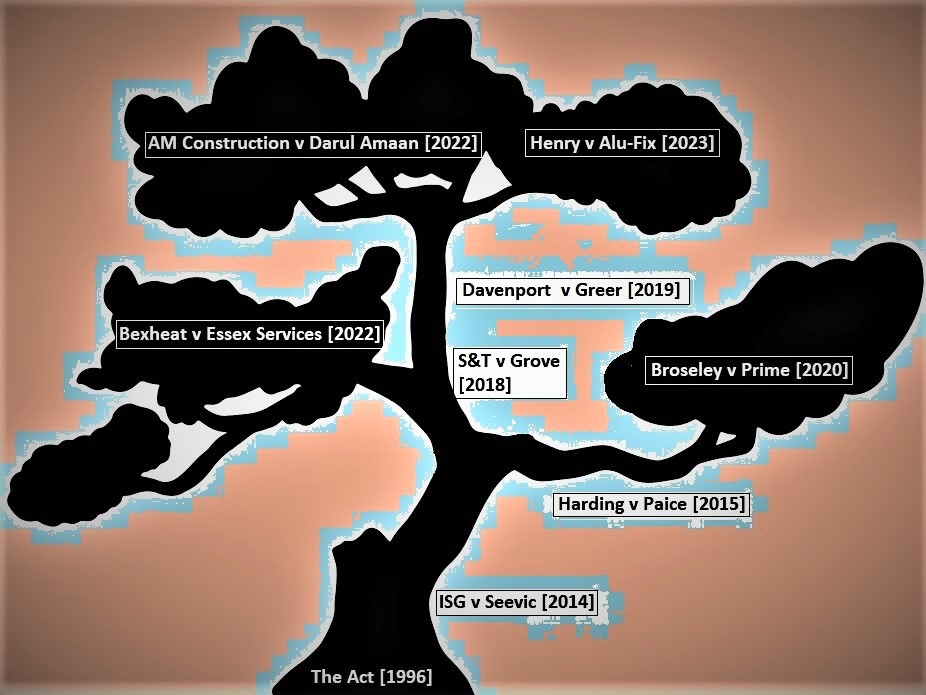

True value proceedings have been around since time immemorial and common place in enforcement proceedings since the Construction Act came in to force in 1998. However, a new type emerged after S&T v Grove [2018] (EWCA) whereby the true value adjudication was permitted following a smash and grab adjudication to value the sums properly considered due in an interim payment.

The true value adjudication was already a feature of final account disputes since an earlier ruling in Paice v Harding [2016]. In that case the Judge referred to the differences between the two types of adjudication as a ‘contract issue’ versus a ‘valuation issue’.

Smash and Grab – Term of Art or Misnomer

Smash and grab – the act of breaking a window and looting the occupant’s belongings. A familiar description among criminal lawyers. Less so amongst commercial lawyers. The first trace of this term appearing in the TCC was in CG Group v Breyer Group [2013] and since then it has permeated payment disputes regarding default payment notices.

The general sentiment is that this terminology is distasteful and fallacious where ordinarily a payee has issued a default payment notice in good faith. Even when, prima facie, it might appear like a ‘smash and grab’ – such as in ISG v Seevic [2014] whereby the true value turned out to be a fraction of the smash and grab value – the fact that the payee’s valuation was wrong is far from compelling evidence of an act of bad faith.

The legal landscape

What have we learnt from recent case law on true value adjudications following smash and grab adjudications – or “TVAs” and “SGAs” as DJ Baldwin described them in Henry Construction Projects v Alu-Fix [2023]? Here is a brief summary.

ISG v Seevic College [2014] was the first in the smash and grab era to draw widespread attention. The adjudicator found ISG was entitled to payment of over a million pounds in respect of its default payment notice. By granting summary judgment to Seevic, Mr Justice Edwards-Stuart disapproved of the subsequent true valuation adjudication stating that the dispute was the same and therefore the adjudicator had no jurisdiction. Effectively, absent a payer’s payment notice the employer was said to have agreed the sum due and that could be corrected in the next interim payment.

Has that principle stood the test of time? Well, following that decision the true value adjudication has unrelented and the courts have debated a great deal on its merits. In Matthew Harding v Paice [2015] EWCA, the dispute was in relation to a final account and on appeal the courts found that the payer can adjudicate to determine the ‘correct’ amount due, even though no payment notice or pay less notice has been served. It should be noted that the principle was specifically in respect of final accounts and even then, fact dependent.

Next in line came S&T v Grove [2018] (EWCA). This was an interim payment dispute which overturned Seevic and established the right to true value adjudication in same interim cycle pursuant to an immediate payment obligation. This aligned the law on final payments with interim payments.

From there, the Courts further grappled with the timing issue of a true valuation adjudication. In M Davenport Builders v Greer [2019] the payment obligations were met before the decision in the true value adjudication. Nonetheless, this proved insufficient and Mr Justice Edwards-Stuart set out the following principles:

“In my judgment, it should now be taken as established that an employer who is subject to an immediate obligation to discharge the order of an adjudicator based upon the failure of the employer to serve either a Payment Notice or a Pay Less Notice must discharge that immediate obligation before he will be entitled to rely upon a subsequent decision in a true value adjudication … That does not mean that the Court will always restrain the commencement or progress of a true value adjudication commenced before the employer has discharged his immediate obligation.”

Recently, in Bexheat v Essex Services Group [2022], there was some further clarity given from Mrs Justice O’Farrell on the timing issue. The judge set out the following principles:

“Where a valid application for payment has been made by a contractor in accordance with the terms of a construction contract falling within the scope of the Act, an employer who fails to issue a valid payment or pay less notice must pay the notified sum in accordance with s.111 of the Act by the final date for payment…

Where a party is required to pay a notified sum following its failure to issue a valid payment or pay less notice, such party is entitled commence a true value adjudication in respect of that sum (but only if it has complied with s.111 of the Act).”

And that brings us to 2023 and those two principles are currently the lie of the land. In AM Construction v The Darul Amaan Trust [2022] the employer started a true valuation adjudication without paying a disputed notified sum. The court concluded that the fact that a notified sum was subsequently found due following an adjudication, this was an absolute bar to any true valuation adjudication being started by an employer.

In Henry Construction v Alu-Fix [2023], before the submissions stage had taken place in the smash and grab adjudication, Henry commenced a true value adjudication. Henry had no grounds to commence the true value adjudication as they had not released their immediate payment obligation. The court rejected the relevance of Henry’s position that there had been a “genuine dispute” as to any purported payment obligation but remarked that had Henry won the first adjudication, the second may well have been valid.

Discussion

I would like to see the courts cast aside the term ‘smash and grab adjudication’ as its continued usage can only be damaging to the industry. Perhaps apt, in the language of Lord Justice Jackson, the courts could adopt the ‘contractual interim payment dispute’ followed by the ‘valuation interim payment dispute’. Or maybe the term ‘notified sum dispute’ would suffice. The term ‘smash and grab’ might then be used metaphorically to describe a contractor making an application in bad faith.

using WordPress and

using WordPress and