This article examines Bilton & Johnson (Building) Co Ltd v Three Rivers Property Investments Limited [2022] EWHC 53 (TCC), an interesting case concerning an application for summary judgment to enforce an adjudicator’s decision. In granting summary judgment, the court systematically dismissed challenges based on alleged breaches of natural justice. The decision serves as a salutary lesson for parties seeking to resist enforcement on procedural grounds and provides valuable clarity on the high threshold required to succeed.

Factual Background

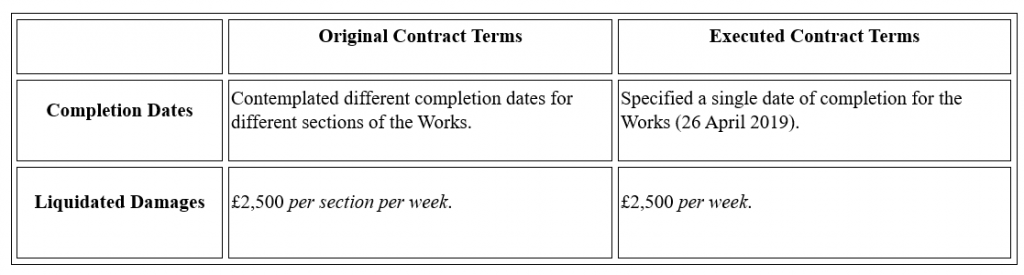

On 10 August 2018, Bilton tendered for the refurbishment works of an industrial estate in Thame, Oxfordshire in the sum of £1,902,633.30. The Form of Tender stated that: “We agree that unless and until this formal agreement is prepared and executed this Tender, together with your written acceptance thereof, shall constitute a binding contract between us”. On 15 August 2018, Three Rivers’ agent issued a written acceptance which formed a binding contract. However, on 9 January 2019, Bilton executed and returned a formal JCT Design and Build Contract 2016. Subsequently, in June 2019, Three Rivers’ agent noticed discrepancies between the two versions and issued an amended contract which Bilton refused to sign. The distinction between these two contracts was critical, as they contained materially different terms regarding completion dates and liquidated damages:

The adjudicator found that the executed contract superseded the original contract and governed the parties’ relationship. The adjudicator had accepted it was arguable that a mistake had been made, establishing a prima facie case for rectification but he critically found that a possible future entitlement to rectification did not permit Three Rivers to deduct damages at the higher rate before the contract was actually rectified. Further, he found that even if the contract was rectified, the proposed rate of liquidated damages would be an unenforceable penalty, finding it “grotesquely out of all proportion“ to Three Rivers legitimate interest.

The adjudicator decided that Bilton was entitled to an extension of time, moving the Date for Completion to 14 November 2019 and that Three Rivers had incorrectly withheld a total of £234,641.56 in liquidated damages based on the original contract rate of £2,500 per section per week. Therefore, the adjudicator decided Bilton was due £228,273.48.

In reaching this conclusion, the adjudicator expressly rejected Three Rivers’ alternative defence that the executed contract should be rectified to reflect the terms of the original contract. He said: “…in any event I do not consider that I am empowered to order rectification of the Contract in the absence of either the Parties’ agreement or cited legal authority for me to do so as an Adjudicator.”

Natural Justice on the Contract Terms

The judgment referred to Balfour Beatty Construction Ltd v London Borough of Lambeth [2002] EWHC 597 (TCC): “If an adjudicator intends to use a method which was not agreed and has not been put forward as appropriate by either party he ought to inform the parties and to obtain their views as it is his choice of how the dispute might be decided. An adjudicator is of course entitled to use the powers available him but he may not of his own volition use them to make good fundamental deficiencies in the material presented by one party without first giving the other party a proper opportunity of dealing both with that intention and with the results.”

Further, Coulson J (as he then was) stated in Primus Build Ltd v Pompey Centre Ltd [2009] EWHC 1487 (TCC): “An adjudicator cannot, and is not required to, consult the parties on every element of his thinking leading up to a decision, even if some elements of his reasoning may be derived from, rather than expressly set out in, the parties’ submissions. But where, as here, an adjudicator considers that the referring party’s claims as made cannot be sustained, yet he himself identifies a possible alternative way in which a claim of some sort could be advanced, he will normally be obliged to raise that point with the parties in advance of his decision.”

Three Rivers argued that a breach of natural justice had occurred because the adjudicator’s conclusion that an original contract was superseded by a second contract was not advanced by either party. Three Rivers claimed this denied it an opportunity to make representations on that precise point, specifically, the lack of any contractual intention to replace the first contract.

The court comprehensively rejected this argument. It said that the core issue of what contractual terms applied had been fully argued by both parties, that the adjudicator’s reasoning was “derived from, rather than expressly set out in, the parties’ submissions” and that applying the principle from Primus did not constitute him advancing a new case that required being put to the parties. In any event, the court found that any alleged unfairness was not material to the outcome, with the adjudicator’s ultimate finding that the signed contract governed the dispute was directly in line with Bilton’s primary case.

Failure to Address the Rectification Defence

Three Rivers’ second challenge contended that the adjudicator had failed to properly determine its rectification defence. It argued that the adjudicator took an “erroneously restrictive view of his jurisdiction” which he had not canvassed with the parties, thereby breaching natural justice. The court dismissed this challenge by demonstrating that the adjudicator had engaged with the defence in a multi-faceted and pragmatic way, finding that the adjudicator correctly identified that the rectification defence was part of the dispute he had to decide.

In respect of the adjudicator’s finding that, in any event, he lacked the power to order rectification, the court approved: “Only a deliberate failure on the Adjudicator’s part to address the rectification defence could avail the Defendant; manifestly there was no such failure. Nor did the Adjudicator act unfairly by failing to alert the parties to his reasoning on the rectification defence before it was finalised and giving them an opportunity to comment. The Defendant raised the defence, briefly, and had a fair opportunity to put forward full evidence, authority and submissions in support of the defence. The Adjudicator dutifully considered and rejected the arguments which the Defendant had considered it appropriate to put forward.”

Conclusion

This case powerfully reinforces the principle that courts will not entertain natural justice challenges based on an adjudicator’s specific chain of reasoning, provided the core issues were properly before them and argued by the parties. A party cannot resist enforcement simply because the adjudicator’s path to a conclusion was not one they had anticipated.

Interestingly, even if the court had found the adjudicator had failed to exhaust his jurisdiction on the ‘rectification’ challenge, it is submitted by the author that this might not have been considered ‘material’ for several reasons, including the adjudicator’s award of an extension of time.

using WordPress and

using WordPress and